Makindo Medical Notes"One small step for man, one large step for Makindo" |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis, or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd. |

Osteogenic sarcoma (Osteosarcoma)

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology

🦴⚡ Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumour of adolescence. It is radio-resistant ❌, so radiotherapy is usually not part of the treatment plan.

📖 About

- Most common primary malignant bone tumour in adolescents & young adults (peak age 15–18).

- Arises in the metaphysis of long bones near growth plates (rapid growth zones during puberty).

- Produces immature bone (osteoid) as its pathological hallmark.

- Most common sites: distal femur, proximal tibia, proximal humerus.

🧬 Aetiology & Genetics

- Genetic predisposition:

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53 mutation) 🧬

- Hereditary retinoblastoma (RB1 gene) 👁️

- Other associations:

- Paget’s disease of bone (older adults) 🦴

- Prior exposure to ionising radiation ☢️

- Pathology: malignant cells producing disorganised osteoid → bone destruction & replacement.

🩺 Clinical Features

- Persistent, progressive pain (often worse at night) 😣.

- Swelling & tenderness around the joint.

- Palpable, firm mass in advanced cases.

- Restricted joint movement; limp if lower limb affected.

- Pathological fracture due to weakened bone 🦴💥.

- Systemic symptoms (weight loss, fever, malaise) usually appear late.

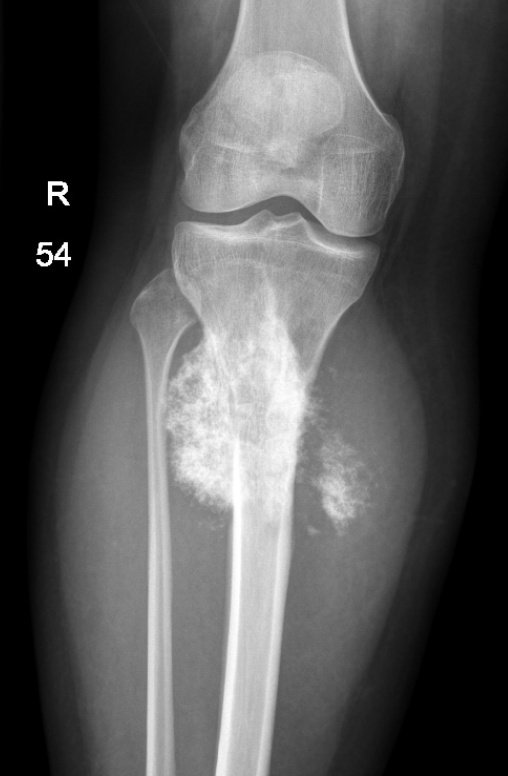

🖼️ Classic Imaging Signs

- Plain X-ray: “Sunburst appearance” 🌞 = spiculated periosteal bone growth.

- Codman’s Triangle: periosteal elevation due to aggressive tumour growth 📐.

- MRI: Defines local extent & soft-tissue invasion (surgical planning).

- CT chest: Essential to look for lung metastases (most common site 🌬️).

🧪 Other Investigations

- Biopsy: Core/open biopsy = gold standard for histological diagnosis.

- Labs: ↑ Alkaline phosphatase & LDH → correlate with tumour burden & prognosis.

- Bone scan: Detects multifocal disease or bone metastases.

💊 Treatment

- Surgery: Mainstay of treatment 🩺✂️

- Limb-salvage surgery now preferred in many cases.

- Amputation still used if tumour encases vital neurovascular structures.

- Chemotherapy: 💉

- Given pre-operatively (neoadjuvant) to shrink tumour.

- Post-operatively (adjuvant) to eliminate micrometastases.

- Common agents: Methotrexate, Doxorubicin, Cisplatin, Ifosfamide (MAP regimen).

- Radiotherapy: ❌ Not effective (radio-resistant).

📈 Prognosis

- With modern therapy: 5-year survival for localised disease ≈ 60–70% 🌟.

- Poorer outcomes in:

- Axial tumours (pelvis/spine/skull).

- Metastatic disease at diagnosis (esp. lungs) 🌬️.

- Poor histological response to neoadjuvant chemo.

🧑🏫 Exam Tip

Remember the triad for imaging OSCEs: Sunburst pattern 🌞, Codman’s triangle 📐, and metaphyseal location near growth plates. Always link osteosarcoma to adolescents with bone pain + swelling and highlight that radiotherapy is not used 🚫.

📚 References

- Oxford Handbook of Oncology

- Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics

Cases — Osteogenic Sarcoma (Osteosarcoma)

- Case 1 — Adolescent with knee pain 🦴: A 15-year-old boy presents with progressive pain and swelling around his left knee, worse at night and not relieved by rest. Exam: firm, tender mass around distal femur. X-ray: mixed lytic–sclerotic lesion with periosteal elevation (“sunburst” pattern, Codman’s triangle). Diagnosis: osteosarcoma of distal femur. Managed with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by limb-salvage surgery.

- Case 2 — Pathological fracture ⚡: A 17-year-old girl presents after a minor fall causing a mid-femoral fracture. History: 3 months of dull bone pain. X-ray: destructive metaphyseal lesion with cortical breach. Biopsy: malignant osteoid production. Diagnosis: osteosarcoma presenting with pathological fracture. Managed with chemo and surgical resection; orthopaedic oncology team involved.

- Case 3 — Metastatic disease 🌬️: A 14-year-old boy with known osteosarcoma of the proximal tibia (diagnosed 6 months ago) presents with cough and breathlessness. CT chest: multiple cannonball pulmonary metastases. Diagnosis: osteosarcoma with lung metastases. Managed with systemic chemotherapy, resection of primary tumour, and palliative resection of lung mets if feasible.

Teaching Point 🩺: Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumour in adolescents, usually affecting metaphyses of long bones (distal femur, proximal tibia, proximal humerus). Key features: progressive bone pain, swelling, pathological fractures. X-ray: sunburst periosteal reaction, Codman’s triangle. Metastasis: commonly to lungs. Management: multi-agent chemotherapy + surgical resection (limb-salvage or amputation).