Makindo Medical Notes"One small step for man, one large step for Makindo" |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis, or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd. |

Sickle Cell Disease

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology

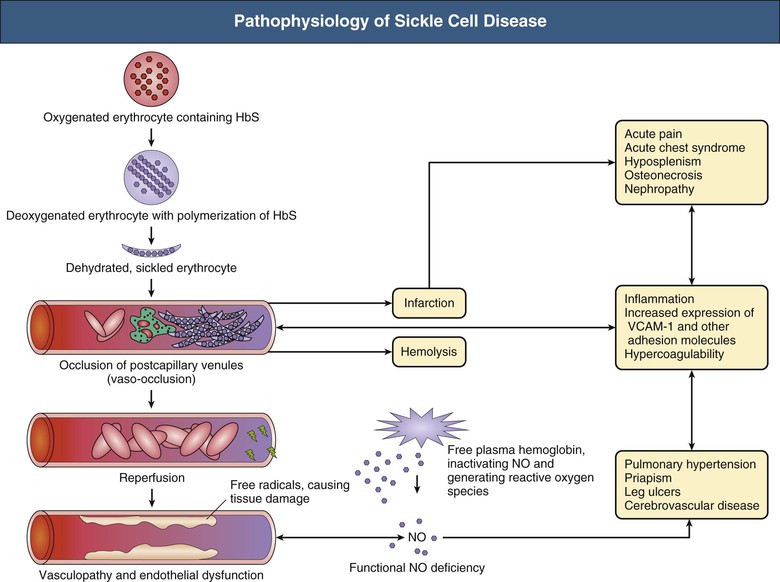

🩸 Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) → Inform haematology immediately if a known HbSS/SC patient is admitted. 🔄 In SCD, red cells become “sickle-shaped” under hypoxic stress → vaso-occlusion, haemolysis, and multiorgan complications.

📖 About

- 🌍 Chronic haemolytic anaemia, mainly affecting people of Afro-Caribbean origin.

- ⚡ Most severe: HbSS (≈70% UK cases).

- 🟡 HbSC: milder but still crisis-prone.

- 🧬 HbAS (trait): usually asymptomatic, but gene carrier & protective against malaria.

- 🆘 Patients often carry a haemoglobinopathy alert card.

🧬 Aetiology

- 🧪 Point mutation: Valine replaces glutamic acid at position 6 of β-globin.

- 🔗 HbS polymerises at ↓ O₂ → rigid, sickled cells → vaso-occlusion + haemolysis.

- 🔍 Diagnosis: Hb electrophoresis or HPLC.

⚡ Precipitants of Sickling

- ⛰️ Deoxygenation (high altitude, hypoxia).

- 💧 Dehydration.

- 🤒 Infection, fever.

- 🤰 Pregnancy, 😰 stress, 🧪 acidosis.

🩺 Types of Haemoglobinopathy

- 🔴 HbSS: severe, anaemic, recurrent crises.

- 🟡 HbSC: milder, vaso-occlusion possible.

- ⚫ HbS/β-thalassaemia: resembles HbSS.

- 🟢 Trait (HbAS): asymptomatic carrier.

👩⚕️ Clinical Presentation

- 🌬️ Acute chest syndrome: fever, dyspnoea, chest pain, hypoxia, falling Hb → ICU risk.

- 🦴 Painful vaso-occlusive crisis: bone pain (esp. long bones, spine, dactylitis in children).

- 🪫 Splenic sequestration: sudden splenomegaly + hypovolaemia (esp. children).

- 🧠 Neurological: stroke from cerebral sickling.

- 🍆 Priapism: prolonged painful erection → urgent input.

- 🦠 Aplastic crisis: parvovirus B19 → profound anaemia.

- 💛 Cholecystitis: gallstones from chronic haemolysis → jaundice + RUQ pain.

🚑 Complications

- 🌬️ Acute chest syndrome.

- 🛡️ Recurrent infections (autosplenectomy → pneumococcus, Salmonella osteomyelitis).

- 🦵 Avascular necrosis (femoral head common).

- 🩸 Renal papillary necrosis, haematuria.

- 🍆 Priapism → risk of erectile dysfunction.

- 🩹 Leg ulcers, hepatosplenomegaly, pulmonary fibrosis.

🔎 Investigations

- 🩸 FBC → anaemia, ↑ reticulocytes.

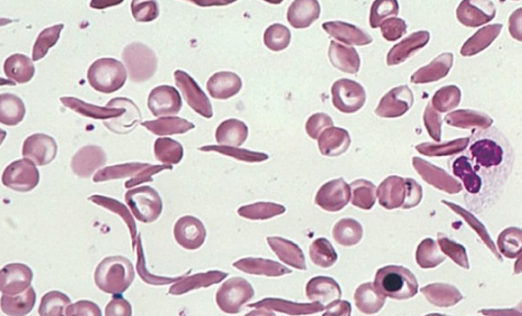

- 🔬 Blood film → sickled cells, target cells.

- 🦠 Sepsis screen if febrile.

- 🌬️ ABG & sats → hypoxia (chest crisis vs PE).

- 🖼️ CXR → consolidation/effusion.

- 🧠 CT/MRI brain → if neurological deficit/stroke.

- 🧪 U&E, LFTs, LDH, bilirubin, haptoglobin → haemolysis & organ function.

💊 Management of Acute Crisis

- 🛑 ABCDE + senior review early.

- 💧 Hydration: IV saline (avoid overload).

- 💊 Pain relief: Morphine within 30 mins, titrate + NSAID + paracetamol. Add laxatives.

- 🌬️ O₂ if sats <95%.

- 🦠 Antibiotics if fever/sepsis (cover pneumococcus/Salmonella).

- 💉 Consider exchange transfusion for: acute chest, stroke, priapism, multi-organ failure (target HbS <30%).

📅 Long-Term Management

- 💊 Hydroxyurea → ↑ HbF, ↓ crises.

- 💉 Vaccinations: pneumococcus, Hib, meningococcus.

- 💊 Prophylactic penicillin in children.

- 🧬 Bone marrow transplantation → curative in selected patients.

📚 Exam / OSCE Pearls – 🚨 Sickle crises are medical emergencies → treat pain + fluids promptly. – 🤒 Always rule out infection. – 🌬️ Chest crisis: O₂ + antibiotics + consider exchange transfusion. – 🍆 Ask about priapism, 🧠 neuro symptoms, 🪫 splenic sequestration in any acute admission.

📖 References

Cases — Sickle Cell Disease

- Case 1 — Vaso-occlusive crisis 🔥: A 19-year-old man with known HbSS genotype presents with sudden severe generalised bone pain, especially in his long bones and back. He is febrile (38.1°C) and tachycardic. FBC: Hb 7.8 g/dL, WCC 15.0 ×10⁹/L. Diagnosis: acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Managed with opioid analgesia, IV fluids, oxygen, and infection screen with empiric antibiotics.

- Case 2 — Acute chest syndrome 🫁: A 24-year-old woman with sickle cell disease presents with pleuritic chest pain, fever, cough, and increasing shortness of breath. CXR: new bilateral infiltrates. ABG: hypoxia. Diagnosis: acute chest syndrome (vaso-occlusion in pulmonary vasculature ± infection). Managed with oxygen, antibiotics, analgesia, and exchange transfusion if hypoxia worsens.

- Case 3 — Stroke in childhood 🧠: A 10-year-old boy with sickle cell disease is brought with sudden right-sided weakness and slurred speech. CT head: ischaemic stroke. Bloods: Hb 6.9 g/dL. Diagnosis: ischaemic stroke due to sickle cell vaso-occlusion. Managed acutely with exchange transfusion and long-term with chronic transfusion programme and hydroxycarbamide.

Teaching Point 🩺: Sickle cell disease is an inherited haemoglobinopathy (HbSS) leading to haemolysis and vaso-occlusion. Key complications include: painful crises, acute chest syndrome, stroke, splenic sequestration, infections, chronic organ damage. Hydroxycarbamide, vaccination, prophylactic antibiotics, and transfusion programmes improve survival.