Makindo Medical Notes"One small step for man, one large step for Makindo" |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis, or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd. |

Basilar artery thrombosis

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology

Related Subjects: |🧠 Acute Stroke Assessment (ROSIER & NIHSS) |⚡ Causes of Stroke

📖 Introduction

Basilar artery thrombosis (BAT) is a rare (<1% of strokes) but highly lethal condition. It results from occlusion of the basilar artery, causing posterior circulation ischaemia. 💀 Untreated, mortality is extremely high. 🔬 Advances in MRA/CTA allow early detection, and mechanical thrombectomy or intra-arterial thrombolysis can be life-saving.

🧩 Anatomy

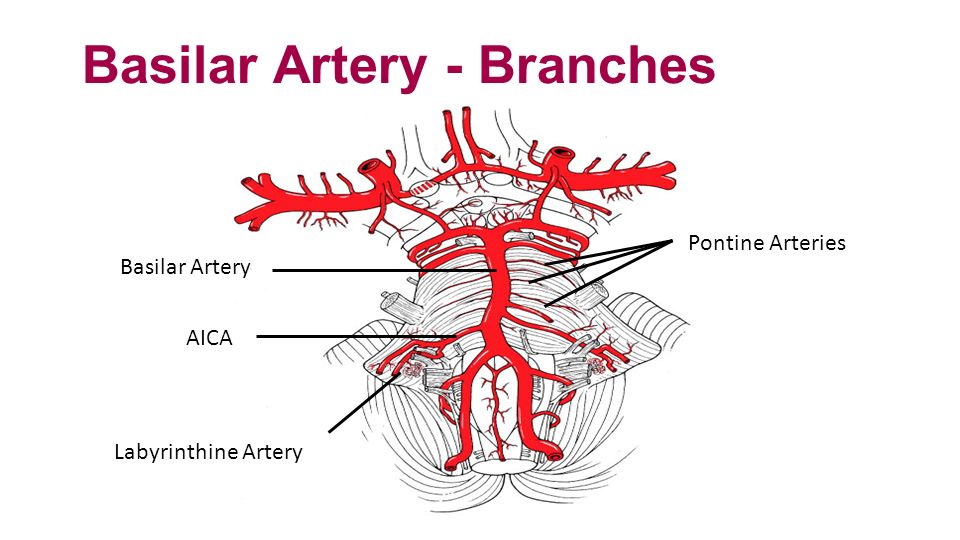

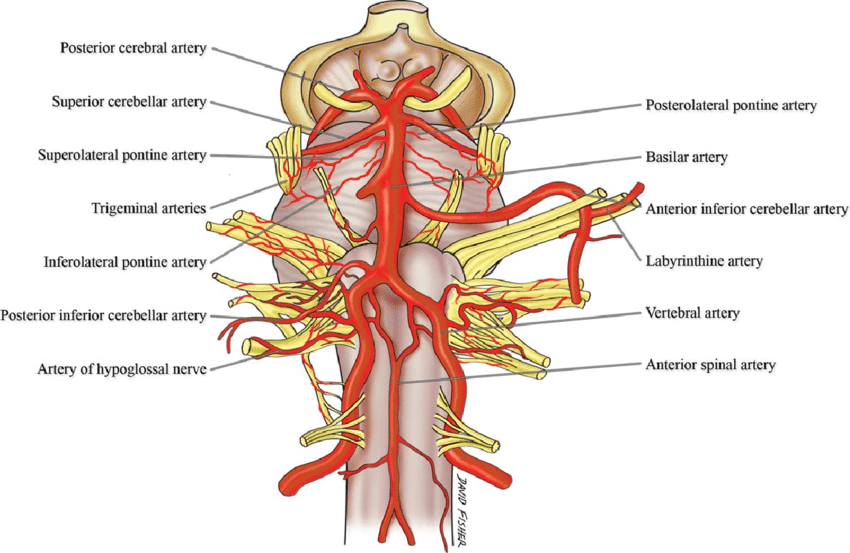

The basilar artery forms from fusion of the vertebral arteries at the lower pons, running along the brainstem before bifurcating into the posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs).

- AICA: Cerebellum + pons

- Labyrinthine artery: Inner ear

- Pontine arteries: Brainstem perforators → tiny but vital

- SCA: Superior cerebellum + midbrain

- PCAs: Occipital lobes, medial temporal lobes, thalami

🧬 Etiology & Pathophysiology

- ❤️ Cardioembolism: esp. atrial fibrillation

- 🫀 Artery-to-artery embolism: vertebral/basilar atherosclerosis

- 🩸 Thrombus in situ: plaque rupture, local clot

- 🪢 Arterial dissection: vertebral → basilar extension

- 🔥 Vasculitis/Inflammation: arteritis, meningitis

⚠️ Occlusion can evolve gradually → progressive brainstem symptoms, or suddenly → catastrophic collapse ("brainstem stroke syndrome").

⚠️ Risk Factors

- Hypertension, Diabetes, Hyperlipidaemia

- Smoking 🚬

- Atrial fibrillation & cardiac emboli

- Cervical artery dissection

- Substance misuse (cocaine)

- Systemic vasculitis / meningitis

- Inherited arteriopathies

🩺 Clinical Presentation

- 💥 Sudden collapse, coma

- 🦽 Quadriparesis/quadriplegia

- 👀 Diplopia (CN palsies)

- 🗣 Dysarthria, Dysphagia

- 🎯 Cerebellar ataxia

- 🎯 Pinpoint pupils (pons)

- 🧊 "Locked-in syndrome" → conscious, vertical eye movements only

🔎 Early signs can be subtle (dizziness, slurred speech) → high suspicion + CTA/MRA is essential.

🧪 Investigations

- 🩸 Bloods: FBC, U&E, LFT, lipids, coagulation

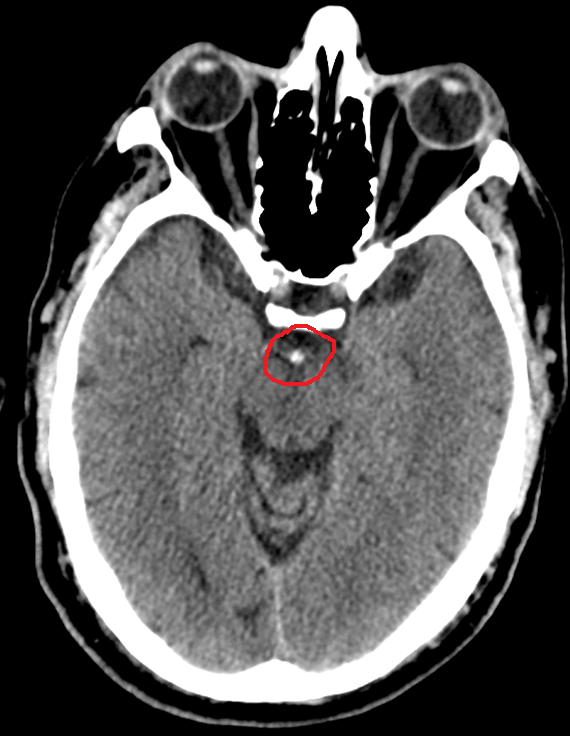

- 🖼 CT Head: hyperdense basilar sign (HDBA)

- 🩻 CTA: confirms occlusion, assesses collaterals

- 🧲 MRI DWI: acute infarcts

- 📉 ECG & Echo: cardiac embolic source

🖼 Imaging Findings

Hyperdense Basilar Artery sign (HDBA) → direct CT clue of clot

Posterior circulation infarcts → brainstem, cerebellum, occipital lobes

📉 Prognostic Indicators

- 🚬 Poor: age, smoking, high NIHSS, BATMAN <7, delayed therapy

- ✅ Good: rapid recanalisation, bilateral PCOMs, NIHSS ≤4 at 48h

🧮 BATMAN Score (CTA)

Posterior collateral scoring (0–10). <7 = poor prognosis. Includes flow in vertebral, basilar, PCAs + PCOMs.

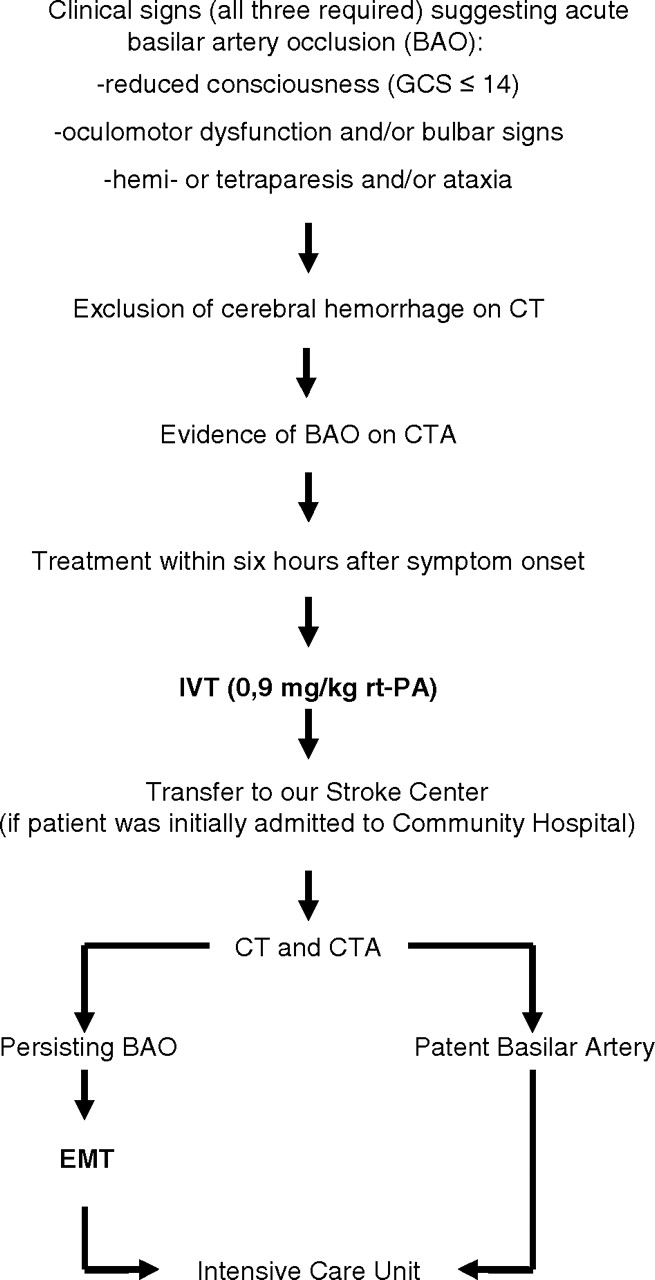

⚕️ Management

- 🛌 Stabilisation: airway, breathing, ICU admission

- 🖼 Imaging: urgent CTA for eligibility

- 💉 IV Thrombolysis: within 4.5h (select cases up to 6h)

- 🧑⚕️ Mechanical Thrombectomy: best option, up to 12–24h if salvageable tissue

- 💊 Antithrombotics: secondary prevention after reperfusion

- ❤️ Supportive: BP, glucose, prevent DVT, manage complications

- 🌅 Palliative: if prognosis grim (locked-in, brainstem necrosis)

📈 Prognosis

❌ Mortality is very high without intervention. ✅ Early recanalisation dramatically improves outcome. ⚡ Survivors often need long-term rehab for motor, swallowing, and cognitive deficits.

📚 References

- Schwartz NE et al. Basilar Occlusion Syndromes. The Neurohospitalist. 2015

- Lindsberg PJ, Mattle HP. Basilar artery occlusion. Lancet Neurol. 2011

- Rangaraju S et al. NIHSS predictors in basilar occlusion. Stroke. 2016

- Kang DH et al. Posterior circulation collaterals & outcome. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016