Makindo Medical Notes"One small step for man, one large step for Makindo" |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis, or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd. |

Thalamic Haemorrhage

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology

Related Subjects: |Subarachnoid Haemorrhage |Perimesencephalic Subarachnoid haemorrhage |Haemorrhagic stroke |Cerebellar Haemorrhage |Putaminal Haemorrhage |Thalamic Haemorrhage |ICH Classification and Severity Scores

🧠 Thalamic strokes can mimic sleepiness rather than coma. They arise from disruption of the thalamus, a key relay for sensory and motor pathways. Early recognition is crucial as prognosis depends on rapid imaging and management.

🔎 Introduction

Thalamic strokes involve an interruption of blood flow to the thalamus, a deep-seated structure acting as a relay centre for motor and sensory signals. They can be ischaemic or haemorrhagic and represent a small but important group of strokes. Clinical manifestations are varied — ranging from sensory loss and hemiparesis to visual field defects, memory impairment, and movement disorders.

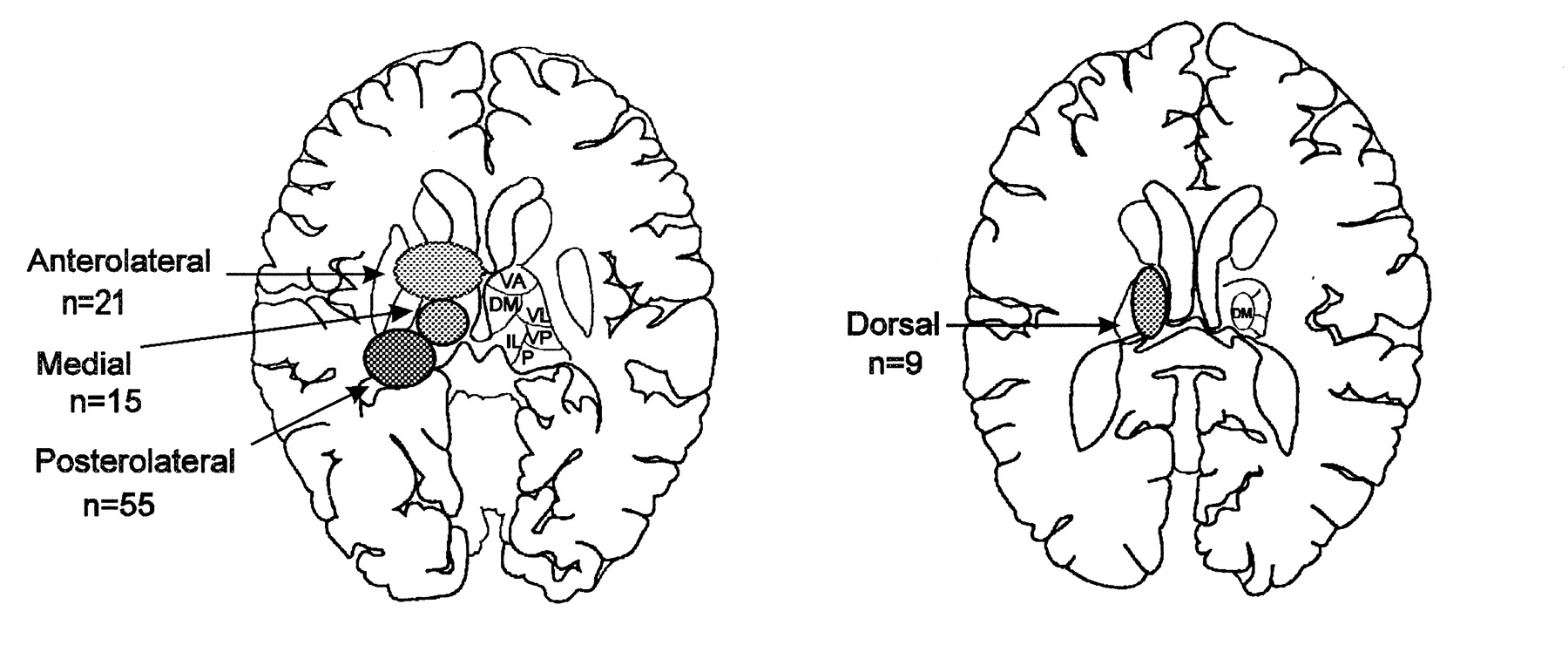

🩸 Anatomy & Vascular Supply

- The thalamus is supplied by small penetrating arteries from the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and posterior communicating artery (PComA).

- Paramedian arteries: from PCA (sometimes via a single artery of Percheron → bilateral thalamic infarcts).

- Tuberothalamic (polar) artery: from PComA → anterior thalamus.

- Thalamogeniculate arteries: from PCA → lateral thalamus.

- Posterior choroidal arteries: posterior thalamus & adjacent structures.

⚠️ Etiology

- Ischaemic infarction: small vessel disease (hypertension, diabetes), emboli, artery of Percheron occlusion.

- Haemorrhage: hypertensive bleeds, amyloid angiopathy, vascular malformations.

- Other: venous infarction (deep cerebral vein thrombosis), neoplasm, inflammatory lesions.

🧩 Clinical Features

- Sensory loss: contralateral hemianesthesia (all modalities).

- Motor weakness: contralateral hemiparesis from internal capsule involvement.

- Thalamic pain syndrome: chronic burning/aching pain weeks after stroke.

- Visual field defects: contralateral homonymous hemianopia/quadrantanopia.

- Oculomotor signs: vertical gaze palsy, light-near dissociation.

- Consciousness: drowsiness/coma in bilateral infarcts (esp. artery of Percheron).

- Cognitive & behavioural changes: memory impairment, apathy, disorientation.

📊 Vascular Territories & Syndromes

| Artery | Clinical Syndrome |

|---|---|

| Paramedian (incl. artery of Percheron) | ⬇️ Consciousness, vertical gaze palsy, memory impairment |

| Tuberothalamic (polar) | Language disturbance, memory issues, apathy |

| Thalamogeniculate | Contralateral sensory loss, hemiparesis, movement disorders |

| Posterior choroidal | Visual field defects, ataxia, hemisensory loss |

🚨 Artery of Percheron infarct: Rare cause of sudden coma with bilateral thalamic and midbrain infarcts. Look for vertical gaze palsy + memory loss — a high-yield exam favourite!

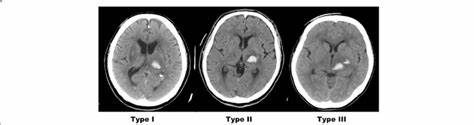

🖼️ Imaging

- CT head (non-contrast): first-line to exclude haemorrhage.

- MRI DWI: best for small acute infarcts.

- CTA/MRA: shows PCA/PComA anatomy, can detect artery of Percheron occlusion.

- DSA: gold standard if vascular malformation suspected.

🧪 Investigations

- Bloods: FBC, U&E, glucose, lipids, clotting.

- ECG ± Holter: atrial fibrillation, arrhythmias.

- Echocardiogram: cardiac embolic source.

- Risk factors: BP monitoring, HbA1c.

🚑 Acute Management

- Ischaemic: IV thrombolysis ≤4.5h (if eligible), mechanical thrombectomy up to 6h (≤24h in selected cases), start antiplatelets once haemorrhage excluded.

- Haemorrhagic: strict BP control, neuro ICU, manage ICP, neurosurgical opinion.

🔄 Secondary Prevention

- Antiplatelets (aspirin, clopidogrel) or anticoagulation if cardioembolic.

- Statins (LDL reduction + plaque stabilisation).

- Risk factor control: BP, diabetes, smoking cessation, exercise.

🧑🦽 Rehabilitation

- Physio: motor recovery, gait training.

- OT: daily living adaptations.

- SLT: dysarthria, dysphagia.

- Pain team: for thalamic pain syndrome (antidepressants, anticonvulsants).

- Psychological support for depression, fatigue, cognitive issues.

📈 Prognosis

- Many recover function, but persistent sensory loss and pain are common.

- Haemorrhagic strokes carry higher mortality.

- Bilateral thalamic infarcts have poor outcomes if coma persists.

📚 References

- Schmahmann JD. Vascular syndromes of the thalamus. Stroke. 2003.

- Adams HP Jr et al. Guidelines for early management of adults with ischaemic stroke. Stroke. 2007.

- Guenego A et al. Artery of Percheron infarct. Neuroradiology. 2015.

🖼️ Images