Makindo Medical Notes"One small step for man, one large step for Makindo" |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis, or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd. |

Air Embolism

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology

💨 Air Embolism occurs when air bubbles enter the bloodstream, obstructing circulation. This can happen during surgery, trauma, medical procedures, or diving accidents 🏊♂️. The severity depends on the volume of air and site of obstruction, with potential for life-threatening complications. 📌 Positioning the patient: Place head down + left side down (left lateral decubitus, Trendelenburg) → traps air in the right ventricular apex, slowing systemic entry.

📌 About Air Embolism

- ⚙️ Mechanism: Air enters venous or arterial circulation → obstructs blood flow → impaired perfusion.

- 🫀 Venous Air Embolism (VAE): Air reaches right heart → pulmonary artery blockage → hypoxia & cardiovascular collapse.

- 🤿 Divers & Decompression: Rapid ascent → nitrogen bubbles (decompression sickness) mimics air embolism.

- ⚠️ Severity: Even 0.5–1 mL in coronary/cerebral arteries can be fatal; 50 mL+ venous air can cause cardiovascular collapse.

🔬 Pathophysiology

- 🩸 Venous entry favoured when site above right atrium → negative venous pressure sucks in air.

- 🚪 Arterial embolism may arise from pulmonary barotrauma or paradoxical embolism via PFO/ASD.

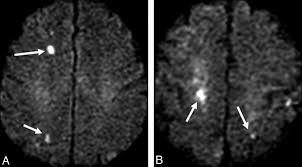

- 🧠 Cerebral and coronary circulation are most vulnerable → stroke-like deficits or MI.

📋 Causes

- 🩻 Surgical Procedures: Neurosurgery, cardiothoracic surgery, or central line manipulation.

- 🪓 Trauma: Chest/neck penetrating injuries or fractured veins.

- 💉 Central Lines & Catheters: Insertion/removal mishaps → most common iatrogenic cause.

- 🤿 Diving Accidents: Poor decompression control → nitrogen embolism/air embolism overlap.

- 💨 Positive Pressure Ventilation: Barotrauma → alveolar-vascular air entry.

🧾 Types

- 🫀 Venous Air Embolism (VAE): → Right heart & lungs → pulmonary hypertension, hypoxia, RV strain.

- 🧠 Arterial Air Embolism (AAE): → Brain, heart, kidneys → stroke, MI, multiorgan injury.

⚠️ Clinical Signs

- 😮 Dyspnoea, hypoxia, cyanosis

- ❤️ Chest pain, arrhythmias

- 🧠 Neurological deficits → dizziness, seizures, confusion, focal stroke

- 📉 Hypotension, obstructive shock

- 💔 Cardiac arrest in severe cases

🔎 Investigations

- 🧪 ABG: Hypoxia ± metabolic acidosis.

- 📈 ECG: RV strain, tachycardia, ST changes.

- 🩻 CXR: Non-specific; may show pulmonary oligemia.

- 🫀 TEE: Sensitive → visualises air bubbles in right atrium/ventricle.

🩺 Differentials

- PE 🫁

- Stroke / TIA 🧠

- MI ❤️

- Tension pneumothorax 🫁

- Cardiac tamponade 💔

🚨 Complications

- 💔 Cardiac arrest (obstructive shock)

- ❤️ Myocardial infarction (coronary embolism)

- 🧠 Hypoxic brain injury (cerebral embolism)

- 🫁 ARDS & respiratory failure

🛡️ Prevention

- 🏥 Procedures: Careful central line insertion/removal, IV filters.

- 🤿 Divers: Controlled ascent & decompression stops.

- 💉 Hospital: Positioning during catheter removal, air-tight line handling.

⚕️ Management

- 🔄 Resuscitation: ABCs, 100% high-flow O₂ (non-rebreather).

- 🛏️ Position: Left lateral decubitus + Trendelenburg.

- 🤐 Intubation/Ventilation: For severe hypoxia.

- 💧 Fluids ± Inotropes: To maintain preload and cardiac output.

💡 Advanced Management

- 💉 Aspiration: Via central venous catheter in RA if accessible.

- 🌊 Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT): Shrinks bubbles, improves oxygenation; gold standard in cerebral/cardiac involvement.

- 🔪 Open Chest Aspiration: Rare; in intra-op cases, direct removal of air from RV or pulmonary artery.

📉 Prognosis

- ⏱️ Depends on speed of recognition & management.

- ✅ Early O₂ + positioning can reverse symptoms.

- ❌ Delayed treatment → permanent neurological injury or death.

📚 References

Case – Venous air embolism after central line removal

A 62-year-old on a surgical ward becomes acutely dyspnoeic and hypotensive minutes after removal of a right IJ central line; she is upright when the dressing lifts and a hissing sound is heard. On exam: tachycardia, hypoxia, raised JVP, and a fleeting “mill–wheel” precordial sound; bedside echo shows RV strain without thrombus. Suspect venous air embolism precipitated by negative intrathoracic pressure. Immediate actions: 100% oxygen (reduces bubble size & treats shunt), place in left lateral decubitus with slight Trendelenburg (Durant’s), apply occlusive pressure dressing over the insertion site, support circulation (IV fluids/vasopressors) and call ICU; if a central line remains, attempt aspiration of air from the right heart. Consider hyperbaric oxygen urgently if neurological deficits or coronary/cerebral involvement suggest arterial gas embolism. Differentiate from PE and tension pneumothorax. Prevention: remove lines with the patient supine/Trendelenburg, during end-expiration or Valsalva, maintain firm occlusive pressure for ≥5–10 min, and use an airtight dressing.